NVIDIA's latest GPU, the Blackwell series, has taken another leap forward with its support for FP4 representations. But where did this idea of leveraging lower precision formats for efficient ML all start? What are the techniques used to amend underflows/overflows despite using reduced precision formats? This series on Mixed Precision Training explores the origins and evolutions of this approach, starting from the OG Mixed Precision Training paper released way back in 2017.

tldr: Normal ML training is done with full precision(FP32). Mixed Precision Training reduces memory requirements to less than 50% by using reduced precision(FP16) for subsets of the model, all without losing model accuracy.

Background:

Neural network training is limited by three factors:

- Arithmetic bandwidth - "How fast can you calculate?"

Number of arithmetic operations that can be performed per unit of time(FLOPS). - Memory bandwidth - "How fast can you move data around?"

Amount of data that can be transferred between the memory and processing units per unit of time(GB/s). - Latency - "How long do you take to complete a task?"

Total time spent on operation to complete.

(Latency; ms) = (time spent on computation) + (time spent on data transfer) + (misc. synchronization overheads, communication latency, etc).

i.e. The fastest training can be achieved by moving and computing things fast with as little overhead as possible.

Mixed Precision Training(MPT) helps mitigate the first two factors–arithmetic bandwidth and memory bandwidth–by simply reducing the precision of data to calculate and move around.

OG Mixed Precision Training: Use FP16 & FP32.

From ("Mixed Precision Training"; Micikevicius et al, 2017; Nvidia & Baidu).

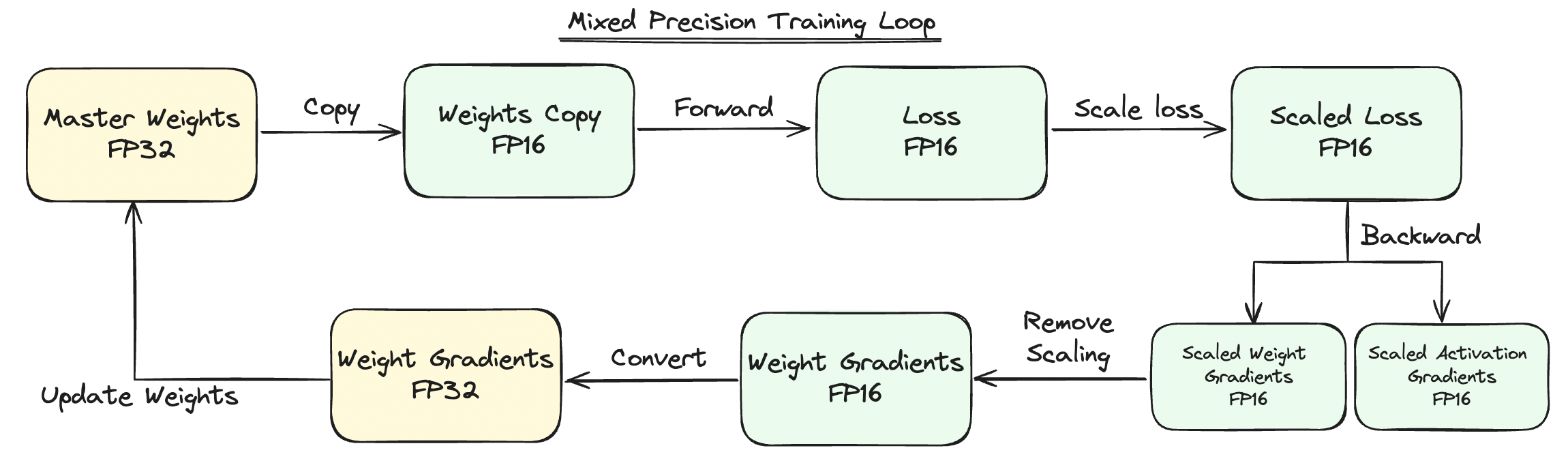

This paper first introduced MPT by reducing all data used during training(weights & activations) into FP16 while only keeping a master copy of weights in FP32. The resulting model halves total memory requirements while experiencing no drops in training accuracy.

Q. Isn't the narrower dynamic range of FP16 an issue?

It is indeed an issue and the paper addresses 3 techniques to amend this. But first, let's see how much of an issue this actually is.

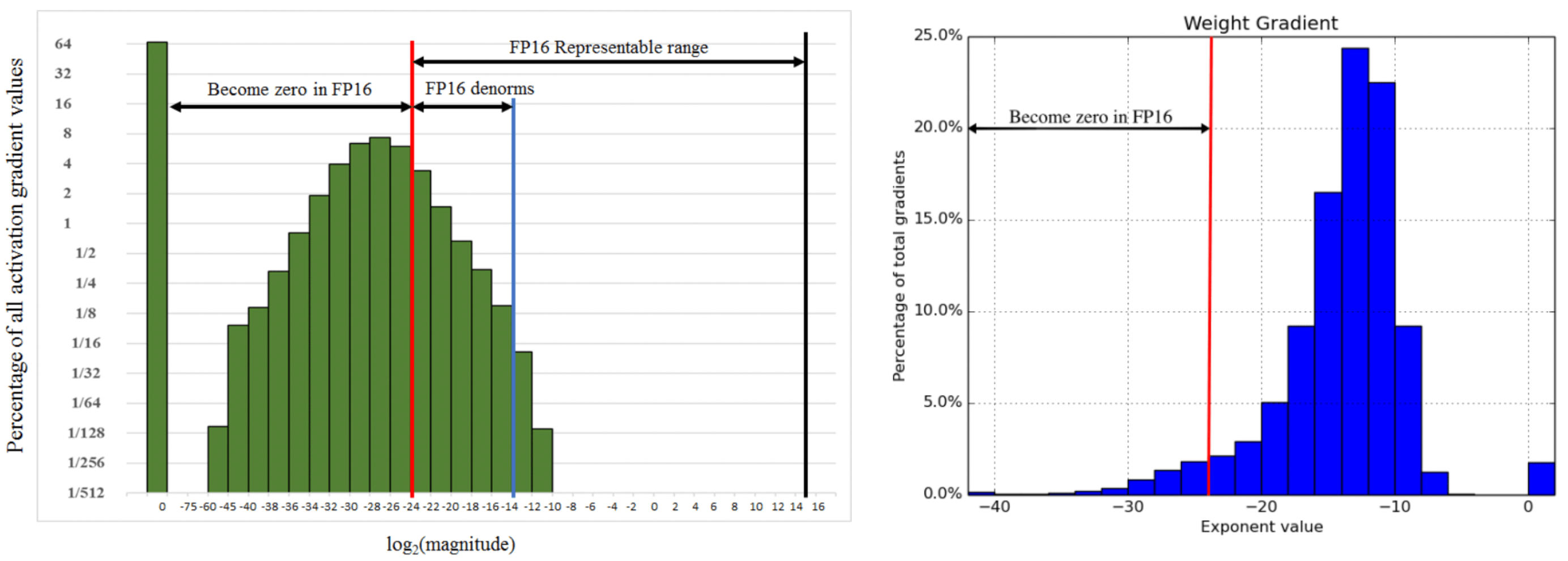

Below are two figures (Micikevicius et al, 2017) that show the amount of underflow that will result for the weights(right) and activations(left).

Approximately 5% of the weight gradient values have exponents smaller than -24 and will become zero in the optimizer. And more than half of the activations will become zero.

Three Techniques to Avoid Underflow of Reduced Precision.

The paper proposes 1) Master copy of weights in FP32, 2) Loss-Scaling, and 3) Accumulating FP16 Products into FP32.

Copy of Master FP32 Weights

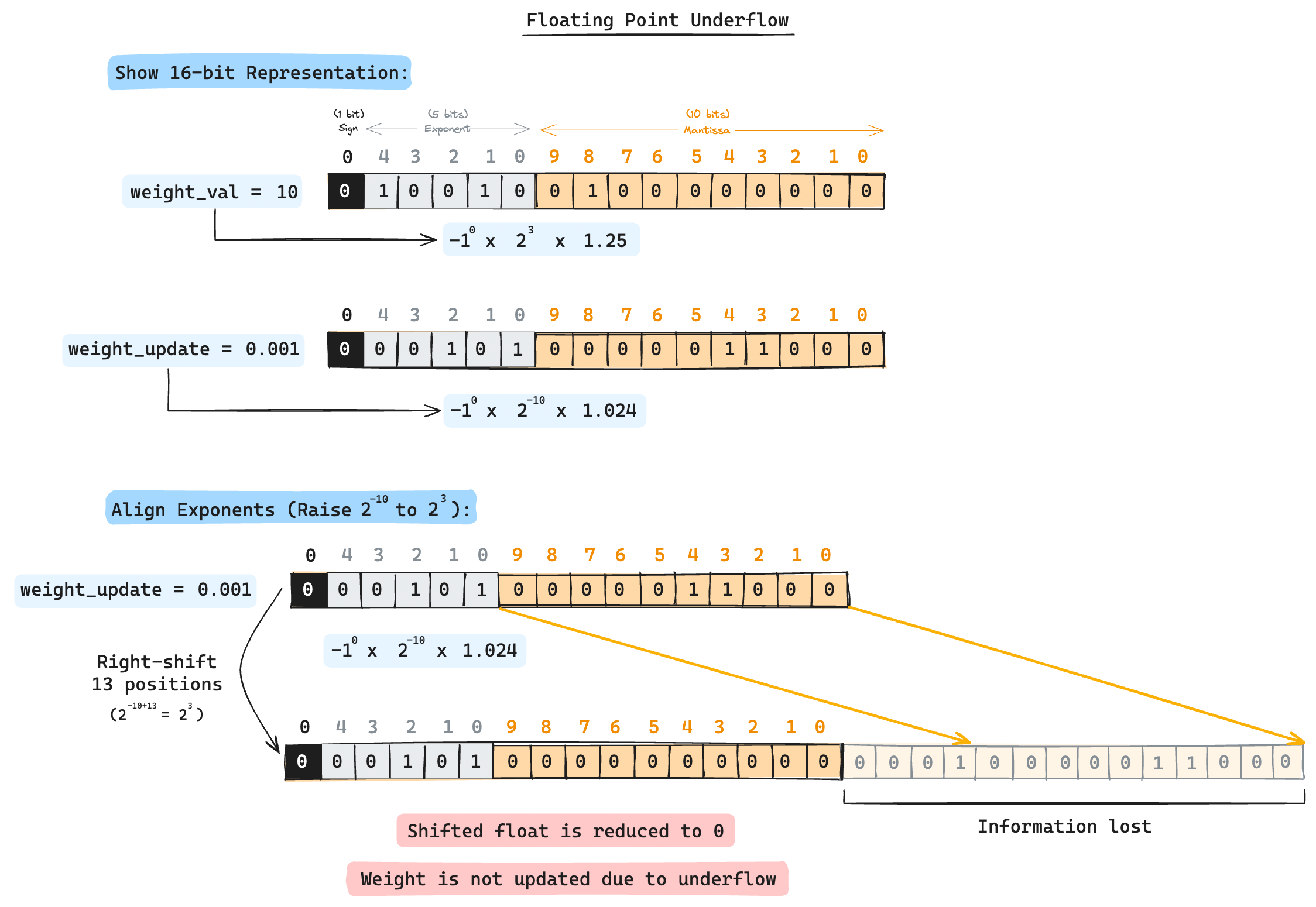

This prevents the case of weight gradients outside the dynamic range of FP16 reverting to zero. However, there's another case we should worry about. Even when the gradients reside within FP16's range, if there is a large difference between the weight value and the weight update value, the weight update value will revert to zero due to the lack of precision when aligning mantissas. An illustrated example is shown below with adding 10 and 0.001.

Generally, for FP16, any weight update value that is 2048 times larger than the weight will result in a FP-Addition underflow as it requires a right-shift of 11 times when there are only 10-bit mantissas. This error would be more profound when working with smaller precisions, but it's amazing how modern GPU cores work with FP8(H100) and even FP4(B100).

Loss-Scaling

Recall that most of the gradients tend to lie outside the representable range of FP16, which quickly destabilizes training.

A naive solution is to scale all the gradients by some factor so they reside within the representable range of FP16, but the paper proposes a simpler solution: scale the loss BEFORE any backprop instead. By the chain rule, all the following gradients will be scaled by the same factor, making this a simple one-liner change.

It is important to remember to unscale the gradients before performing the weight update. So technically it is a two-liner change instead of one.

Accumulating FP16 Products into FP32

The paper says the stable training of some models required accumulating partial products of FP16 vector dot-products into FP32 to prevent performance drops. Solutions to this is a gray area where joint efforts in software and hardware advancements are made.

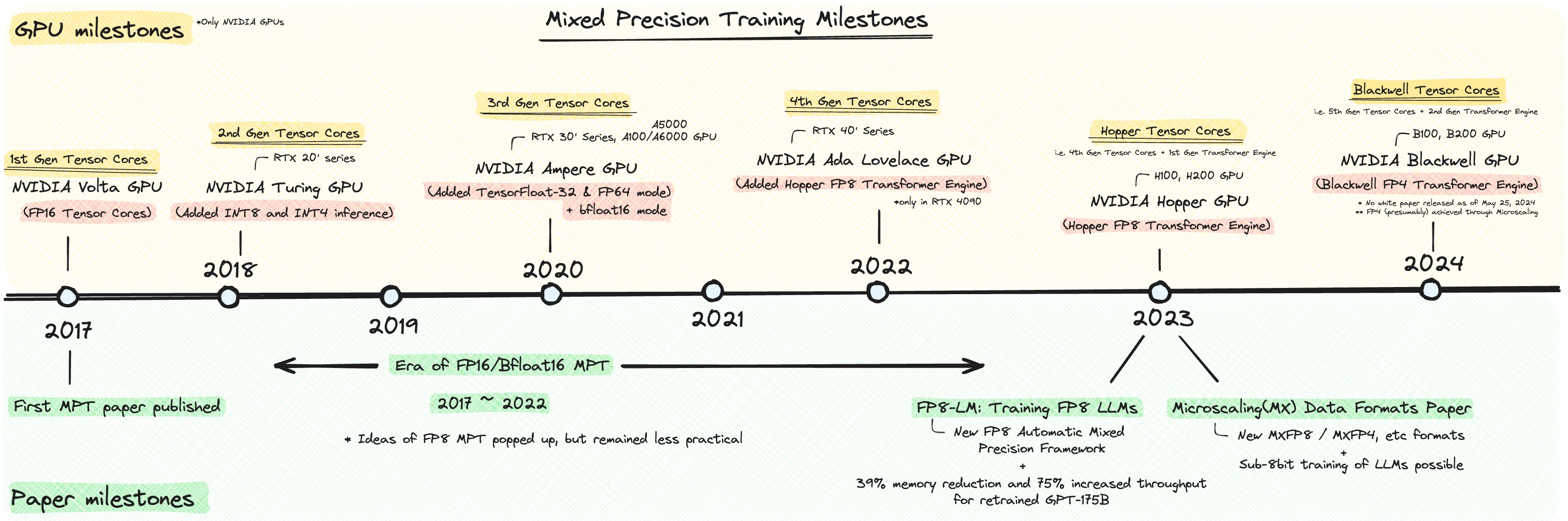

First, hardware advancements were inventing specialized GPU cores that support FP32 accumulations of FP16 inputs. This was first introduced in 2017 with NVIDIA's Tesla V100 GPUs(1st Gen Tensor Core). A series of NVIDIA's Tensor Core evolutions following this is an interesting story of its own. NVIDIA's SOTA GPU in 2024, the B100/B200 built with the Blackwell architecture, now carries 5th Gen Tensor Cores along with a 2nd Gen Transformer Engine that supports FP4(how FP4 is achieved is for another post, but the tldr is Microscaling Data Formats).

Although this paper did not cover optimizations in software for MPT, separate implementations of gradient accumulation, optimizers, and tensor parallelisms are necessary for efficient MPT execution in models with more than a billion parameters. This is also for another post where I will look at advanced mixed precision training techniques(the recent Microsoft's FP8-LM paper and NVIDIA's Microscaling Data Formats).

Downsides of Vanilla MPT

Memory of Optimizer States are Not Reduced

Most modern NNs uses the Adam optimizer to train, which has to keep track of the 1st and the 2nd order gradient moment. This is quite expensive, but vanilla MPT does not address reducing these.

Increased Complexity due to Reduced Dynamic Range

Techinques like loss-scaling mitigate the reduced dynamic range of FP16, but this increases complexity in the training pipeline. This is why the the BF16-FP32 MPT scheme was used more commonly over FP16-FP32 scheme as BF16 covers the same dynamic range with FP32.

References

[1] Micikevicius et al. 2017. "Mixed Precision Training."

[2] White Papers for NVIDIA's Volta, Turing, Ampere, Ada Lovelace, Hopper Architecture.